Most countries in Europe have places where they celebrate their bizarre old traditions. But Britain, despite its rich history, has no properly funded institution where people can research and celebrate our native traditions and vernacular arts.

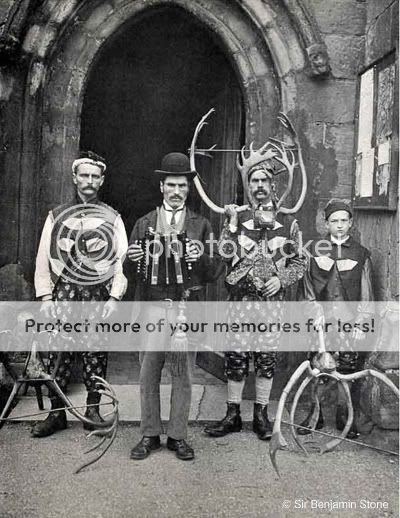

Simon Costin is a remarkable individual who has devoted his life to the accumulation of information and artefacts relating to ancient rites and festivals that occur around these isles every year, some of which are centuries old.

"I intend to establish a permanent collection and national exhibition centre that celebrates and promotes the Folk Culture of the British Isles" he claims. But for now, his museum is on the road. He takes his caravan of artefacts and books around the country to various village fetes in an effort to spread information about these fascinating traditions before they are lost.

Why is it Britain doesn't already have a museum of folklore?

Simon: I suspect there are a number of reasons for our not having any kind of permanent research facility here in the UK. Firstly, the very subject of folklore is perhaps a difficult one to be represented within a museum context. It would come under the heading of 'Intangible Heritage'.

There are very few objects or representative artefacts associated with our annual customs that are not either still in use or that are only constructed for the duration of the event and are then destroyed. Things such as the figure of the Jack from May Day's Jack in the Green, Well Dressing's, Garlands, Lewes Bonfire figures, Punkie Day carved turnips etc, all only exist while the festival is happening. This presents a problem for museums. Should the objects themselves be sourced and preserved in some way? Is there legitimacy if replicas are being made?

So there is a problem from a curatorial point of view as to the kinds of objects that can and should be displayed. This may have discouraged people from tackling the subject in the past.

Another reason could be the way the media has trivialised folk customs in the press, only choosing to highlight the nation's ambivalent attitude towards Morris dancing, or reporting on the casualties of cheese rolling for instance. There have been very few in depth reports, possibly because lazy journalists find it easier to ridicule than study.

Do you think that interest in folklore is tainted by political associations?

Simon: Recently, far right groups such as the BNP, have taken to selling the CD's of various folk musicians at their meetings and attaching spurious meanings to 'Traditional' British songs. This has prompted the formation of a group called Folk Against Fascism which has gained a strong following within the folk community, who are keen to point out that they have absolutely nothing in common with the ideology of the far right.

That the playing of traditional music should be co-opted by a group such as the BNP is of no surprise and it could be argued that in Britain today, anything deemed to be a celebration of certain parts of the UK's national culture has been tainted by the far right, to the point where even the word 'British' carries negative undertows. That can be said of any national symbols which become corrupted by political groups.

Folklore is something that is created by the people living in a specific culture and is a universal phenomena with many cross overs with other nationalities. After all, it deals with universal themes; the coming of summer and the beginning of winter, celebrations of life and memorials for the dead. The origins of that most British dance form, the Morris, are thought to have derived from the Morrish dances of North Africa. St. George was possibly a Roman or a Turkish solider who never even visited the UK. Small minded political groups who would deny this world view do so by showing their ignorance and intolerance.

*Note from STJ - Simon may not be aware that St. George was a Greek speaking Roman born 1000 years before the Turks conquered Byzantium! He was NOT Turkish! Also the theory that Morris dancing is based on dances of the Moors is not proven and is based only on the fact the words look similar. Even if the word Morris is derived from the word Moorish, that is not necessarily because the dances are related, and may be because the dance is based on a Spanish dance after the Reconquista, which celebrated the eviction of Moors from Europe...or the words may be unrelated entirely!

How is folklore relevant to British people today?

Simon: Folklore can be said to be a body of traditional belief, custom, and expression, handed down largely by word of mouth and circulating mostly outside of commercial and academic means of communication and instruction. Every group bound together by common interests and purposes, whether educated or uneducated, rural or urban, possesses a body of traditions which may be called its folklore.

Folklore is reflected in everything from the names we bear from birth to the names of our local pub; The Green Man for instance. Folklore is the slang we use, the secret languages of gangs from school children to guilds and masonic groups. It is the shaping of everyday experiences in stories swapped around the kitchen table or told on blog sites. Folklore can be a roadside shrine to commemorate a killed pedestrian or the massive public display formed when Princess Diana died. Folklore is the cry of fox-hunters as they ride across a field and the weather lore of a farmer. It is scrawled on urban landscapes by graffiti artists or woven into the fabric of churches, mosques and temples. Folklore is community life and values, artfully expressed in myriad forms and interactions. Universal, diverse and enduring, it enriches the country and makes us a commonwealth of cultures.

What is your favourite custom/legend in British folklore?

There are far too many to mention but some of my personal favourite customs would have to be Padstow on May Day, the Hastings Jack in the Green Festival, the Barrel Burning in Ottery St. Mary and Lewes Bonfire.

Can you tell us one of the most unusual things you have encountered while touring?

There was nothing particularly unusual as such but certainly one of the most heart warming was the huge amount of support the project was shown from the many thousands of people who visited the caravan and the way that everybody said the same thing, 'Why is it that British people don't seem to value their native customs and traditions like other people in Europe do?'

So what plans do you have for the museum in 2010?

I'm planning a series of mini museum exhibitions which would ideally be situated in various houses which are open to the public. The first will be at Port Eliot in Cornwall, where they have the Lit Fest in August. Each show will deal with the folklore of the region and take one or two of the festivals which take part in that area and look at their history and development.

Then at the end of May, opening on the 29th, is an exhibition featuring work by the various artists who have been involved with the museum project to date such as Jonny Hannah, Mark Hearld, Clare Curtis, Riitta Ikonen, Tamsin Abbot etc. This will be at the Hexham Art Gallery for the Folkworks Hexham Gathering.

The caravan will be appearing at the Ditchling Fair on the 19th June.

There's to be a big folk concert in mid October probably at the Union Chapel although this has yet to be sorted out. This will be done under the museums music umbrella.

There are also going to be a series of mini museum exhibitions opening across the UK, the first being at Port Eliot in Cornwall on 3rd April. Then there's an art show at the Hexham Gallery on May 29th which runs for a month. The caravan will be making an appearance at the Ditchling Festival and the Compton Verney Summer weekend. In October there will be a large concert to raise awareness of the project in London.

Check out The Museum of British Folklore website to learn more

http://museumofbritishfolklore.com