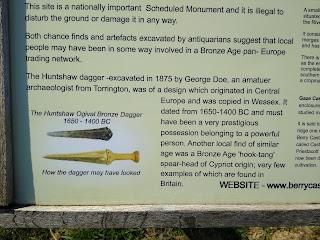

This blog post explains the significance of the barrows of Darracott moor in North Devon and the discovery in 1875 of a dagger in barrow number 2, dubbed the Huntshaw dagger, which was recreated by Neil Burridge in 2025.

In this video I explore the Bronze Age burial ground of Darracott moor

in Huntshaw, Devon. The largest barrow has a road going straight over

it. Another barrow contained a dagger which is in the museum in Exeter. Below I have included

the original lecture notes regarding the two excavations of the 19th

century.

In this video I look at the significance of Cornwall and Devon to the European Bronze Age and I show the recreation of the Huntshaw dagger by the smith Neil Burridge.

EIGHTEENTH REPORT of the Committee, consisting of Mr. P. F. S. Amery, Rev. S. Baring-Gould, Dr. Brushl Mr. R. Burnard, Mr, Cecil M. Firth, Mr. J. Brosling Rowe, and Mr. R. Hansford Worth (Secretary), appointed to collect and record facts relating to Barrows in Devonshire, and to take steps, where possible, for their investigation.

Edited by R. H. WORTH, Hon. Secretary.

(Read at Great Torrington, August, 1899)

Your Committee's Report this year deals with the exploration of certain barrows on Broad Down, near Honiton; the exploration of barrows on Raddick Hill by Mr. Barnard; and of a barrow at Torrington by Mr. G. M. Doe.

EXAMINATION OF A BARROW IN THE PARISH OF GREAT TORRINGTON.

This barrow is one of a series of five, two of which were opened in 1875, and were made the subject of a paper by my late father, read by him at the meeting of this Association here in that year.

The one in question is much larger than any of the others, being from 70 to 80 feet in diameter, and from 4 to 5 feet high. As, however, the highway passes over it, it has probably been considerably lowered. The accompanying plan will show the relative position

of this barrow to its companions. The exploration was commenced on the 26th June last by digging a trench on the north-west side at right angles to the road. In a very short time the workmen came on a mass of whitish grey clay with irregular layers of charcoal, in some places more than an inch in thickness, with here and there a stone which appeared to have been subjected to the action of fire. This lay on the natural clay of the surrounding land. On getting near the centre of the barrow a layer of very different character was discovered. This extended for about 24 feet, and was of varying thickness, from 3 to 14 inches. A thin layer of the greyish white clay with the streaks of charcoal was spread under it, and it was capped over with the same, the streaks and masses of charcoal in this capping of clay being very distinct, and appearing to follow the curve of the barrow. The layer in question consisted of fine reddish earth mixed with burnt matter of a totally different composition from that of the charcoal in the clay. A few small stones which seemed to have been burnt, together with small pieces of quartz, were interspersed in this mass, one being a good-sized rock crystal, and in places pieces of blackened burnt bones were embedded. Parallel. with the road, and at the foot of its boundary hedge, was a perfectly straight line of loose "acre stones," a foot in width and height, which ran through about the centre of the barrow for a length of 60 feet, and on the level of the ground. These stones may have been placed for drainage purposes when the road was made, as they passed through the clay, etc., of the barrow, the layers of which were continued on each side of the stones. On reaching the hedge the trench was discontinued, and the centre of the barrow was cleared away to the ground level, which was carefully examined, but without finding any traces of its having been previously disturbed. After working for a week lack of funds prevented further exploration, but it appears not improbable that the actual interment consisted of the mass of burnt matter and bones. It may be, too, that at the making of the road the barrow was disturbed; nevertheless it has only been very partially explored.

There was no indication of a capping of stones around this barrow, as in those previously opened in 1875. A piece of rusted iron 3 inches long, 1 inch wide, and about inch thick was found imbedded in the clay, etc., in the centre of the barrow, but as it was very near the line of stones before mentioned, it may have got there when the road was: made. (GEORGE M. DOE.)

This second excavation report concerns Barrows 1 and 2, the latter of which contained the Huntshaw dagger.

DOE, G.M. The Examination of two Barrows near Torrington. Trans. Dev. Assoc., 7,102-105 (1875).

THE EXAMINATION OF TWO BARROWS NEAR TORRINGTON.

BY GEORGE DOE.

(Read at Torrington, July, 1875)

In the year 1867 a partial examination of two barrows, situated in the parish of Huntshaw, about two and a half miles from the town of Great Torrington, was made by my friends, the late Mr. Henry Fowler and Mr. Samuel Pearce; and an interesting paper, relating chiefly to the eastern barrow, was read by Mr. Fowler at the meeting of the Devonshire Association held at Barnstaple in that year, which concluded thus:

"Our want of success in finding any such remains as urns or cists may be attributed to the possible fact, that they were placed in some part of the bed of the barrow out of the centre; for in such a case it is evident that numerous cuttings might be made without coming across them. We have hopes, therefore, that some remains will still be found, and the more so as the perfectly undisturbed state of the portions already examined precludes the idea of the barrow having ever before been opened."

Subsequently to the Barnstaple meeting, Mr. Fowler and I had frequent conversations on the subject; and when it became known that the Association would meet at Torrington, we decided on making a thorough examination of the barrows. with a view to the production of a sequel to his paper. Had his life been spared, I should have remained in the background, and an account of the further exploration of the barrows would probably have come from the able pen of Mr. Fowler; but as that could not be, I have felt it an almost religions duty to offer this imperfect effort as my humble tribute to his memory.

The necessary permission of the Hon'ble. Mark Rolle, the landowner, and of Mr. Webb, the tenant, having been obtained, workmen were engaged, and operations commenced few weeks since, under the intelligent superintendence of Mr. Alexander McKelvie, the district highway surveyor, at the western extremity of the western mound (into which a short cutting had been made in 1867, as shown by dotted lines on the accompanying plan), and continued for two days, during which rather more than a half of the mass was removed without any further result than a confirmation of Mr. Fowler's statement, that it was composed almost entirely of one homogeneous mass of clay, with occasional streaks of charcoal, covered by a capping of stone. The clay, which could not have been found on or very near the spot, had evidently been worked or puddled. It could be cut as easily as cheese, being quite free from stones or grit, and varied from a whitish-grey to a bright orange colour; but the streaks of charcoal contained occasional small pieces of brittle red stone, which appeared to have been burnt with the charcoal.

On the third day the workmen had not cut far into the eastern half, when they came upon a rounded heap of stones, measuring ten feet from north to south, and twelve feet from east to west at the base, and four feet in height, the top being three feet below the surface of the harrow. A careful removal of these stones-which appeared to have been "acre stones, and were as clean as when first collected-revealed, in the centre of the heap, a small empty chamber, so rudely constructed that it fell in on the displacement of the covering stones. At the west of this, but on a lower level, another chamber was discovered about eighteen inches square, and nearly a foot in depth, covered by a stone of the same kind as, but much larger than those forming the pile. This chamber was nearly filled with fragments of burnt human bones, and decomposed matter, which may perhaps be the remains of a cloth or skin in which they had been wrapped. Nothing else was found in this chamber, which was floored with flat stones placed on the original surface of the land; nor was any further discovery made among the stones, nor in the mound, the outer and less elevated parts of which were carefully probed with an iron bar. The case with which the clay had been pierced suggested that in the exploration of the eastern mound (through which a cutting had been made in 1867, as shown by dotted lines on the plan) considerable labour might be saved; and the iron bar was accordingly sunk again and again into the portion of the mound corresponding with that under which the interment had been made in its western neighbour. After numerous trials, a spot was at length reached where the gentle insinuations of the iron were arrested at a depth of about two feet, A circular excavation was then made through the capping of clay and the underlying beds of earth and charcoal, which soon brought to light a heap of stones similar to that already described, except that it was circular, with a diameter of eleven feet at the base, and that there was a slight depression or sinkage in its northern half. After the removal of about one half of the heap, pieces of burnt human bones, mixed with ashes and earth, were found between the stones, gradually increasing in number towards the south, where, in a small imperfectly-constructed chamber, was discovered a flat mass of damp leaves, so perfect that they were immediately recognized as oak and beech. Whether they originally formed a chaplet, or in what other form, or for what purpose they were placed there, I will not hazard a speculation. A little further towards the south one of the workmen observed something pointed protruding two or three inches, which he tried to pull out, but fortunately he was unable to do so. The stones above it having been carefully removed, a bronze dagger, which at first sight I mistook for a spear head, was disclosed lying on a flat stone with its point towards the east. Adhering to each side of it were found some very thin pieces of decayed wood, which undoubtedly had formed part of the sheath. They have been preserved; and a more minute inspection of them will, I believe, confirm this view. At the broad end of the blade. are three rivets, by which it had been attached to a wooden handle, the shape and grain of which may be distinctly traced on each side. A small quantity of decomposed wood, in which were found two rivet-heads, extended a few inches over the face of the stone on which the weapon lay; but no trace of a staff could be seen. The dagger is nine and a half inches in length, and two and a quarter inches in width at its broadest part, becoming narrower by a double curve of each edge towards the point. Its present weight is barely eight ounces; but it must have become lighter by the corrosion of its surface, which, however, is still in a wondrously good state of preservation. About a quarter of an inch from the edge two sunk lines, forming a thread, surround the blade, the space between the outer line and the edge being fluted like a modern sword.

Similar daggers are figured in Mr. Llewellyn Jewitt's Grave Mounds and their Contents, p. 132, and in Mr. W. Copeland Borlase's Nenia Cornubia, p. 236; both of which appear to be far more imperfect than the one I have attempted to describe.

As no interment was discovered in 1867, our late operations drew down some contempt and pity from outsiders. The workmen were almost ashamed to undertake the job, because their predecessors had been ridiculed for their pains. One gentleman made the flattering remark, that those who talked of opening the barrows must be either knaves or fools; another attributed the mounds to some enterprising brick maker, who had come to grief, and stopped his works; a third referred them to the old charcoal-burners; another knew that they had been made for a pleasure-ground; whilst one fully charged with English history offered a solution of the mystery by suggesting that they were thrown up during or after a battle in the time of the Great Rebellion.

It may be easily imagined, then, how gratifying was the discovery which has thrown some light on what was previously veiled in obscurity. To my mind there is now not a shadow of a doubt that these barrows were erected by our Celtic ancestors before the Roman occupation of Britain, and during the period designated by archaeologists as the Bronze Age. Should any doubts, however, be entertained on this point, they will, I believe, be dispelled by a perusal of Sir John Lubbock's learned exposition of the reasons why our bronze weapons cannot be referred to the Romans, in the first chapter of his Pre-historic Times. But the dagger, which as a specimen of art-manufacture would not be discreditable to the present century, was probably the handiwork of a race of higher civilization than the builders of the barrows could lay claim to, and imported by one of the merchant adventurers who in that early age visited the tin-producing counties of Cornwall and Devon.

I may add that the investigation of these barrows has afforded another proof of the necessity for examining every part of a sepulchral mound before passing judgment on its character and contents. It is a curious fact that each of the cuttings made in 1867 went within a foot of the interment.