To gain a deeper understanding of medieval Icelandic stories called sagas, historian Tom Rowsell journeys to Iceland, immersing himself in the landscapes that inspired these tales. He rides native horses across the fells, bathes in hot springs, and traces the footsteps of legendary Viking heroes like Eirik the Red and Egill Skallagrimsson.

Showing posts with label sagas. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sagas. Show all posts

Sunday, 27 April 2025

Sagas of the Raven Land: Viking History Documentary

Labels:

ancient history,

asatru,

documentary,

European film,

european history,

germanic paganism,

history documentary,

iceland,

independent cinema,

sagas,

travel

Location:

Iceland

Friday, 13 March 2020

How to receive a visionary dream according to pagan sources

The video specifically looks at an irish rite known as Imbas forosnai performed by elite seer poets known as Filíd, also the tairbfheis, a rite to determine the High king at the Hill of Tara. In Wales there were the awenyddion and in Scotland they had a pagan rite of prophecy called Taghairm. I also look at several Anglo-Saxon and Norse Icelandic saga sources discussing Ulfhednar, Hammramr, Elves, haunted barrows and seers and compare them with the dreams described by Homer and Pausanias in Ancient Greece.

Sources:

Chadwick, N., ‘Dreams in Early European Literature’, in: Carney, James, and David Greene (eds), Celtic studies: essays in memory of Angus Matheson 1912–1962, London: Routledge, 1968. 33–50.

Martin Martin A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland (1703)

O Rahilly, T. F., ‘Early irish history and mythology’ (Dublin 1946)

Ramos, Eduardo, ‘The Dreams of a Bear: Animal Traditions in the Old Norse-Icelandic Context’ (2014)

Tendulkar, S. and Dwivedi, R., “Swapna’ in the Indian classics: Mythology or science?” (2010)

Vaschide and H. Piéron, ‘PROPHETIC DREAMS IN GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITY’ (Oxford : 1901)

The Wooing of Emer by Cú Chulainn (Author: [unknown]), p.303 (paragraph 78.)

Labels:

"anglo saxons",

Ancient Greek,

aryan,

barrows,

burial mounds,

Celtic mythology,

dreaming,

dreams,

eddic poetry,

hindu,

hinduism,

homer,

indo-european,

Norse mythology,

Paganism,

rigveda,

sagas,

Viking,

Viking Age

Saturday, 8 February 2020

Góa month and góiblót - February, March or April festival?

|

| Frigg weaves |

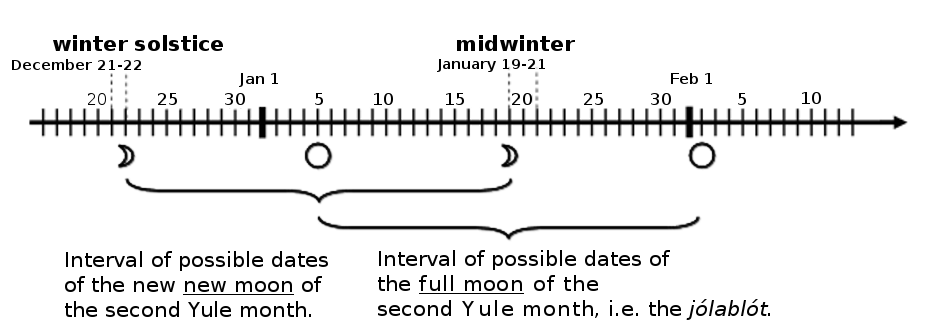

While some modern heathens choose to match ancient Germanic festivals with the Gregorian calendar, others try to stick to the lunar-solar calendar the Germanic people observed.

There are some problems calculating Góa month in either case, due to lack of sources on the festival. The month of Góa is alleged to have been the penultimate month of winter, according to the old, Norse calendar used in Iceland. According to some Icelanders, góiblót took place in late February - but if we follow the lunar-solar model then it would have been on the full moon, because the full moon marks the high festival of each month, and the new moon marks the start of the month, making the start of this year's Góa month either 23rd Jan, or 22nd Feb, ending either 22nd Feb or 23rd March 2020 - with the final month of winter ending in April when the rites of the start of Summer were held - associated with Easter-month in Anglo-Saxon England and all the variant May day celebrations across Europe.

So February seems to match up well enough for the dating, although I am unsure where the claim it is the penultimate month of winter originates. I know of two sources that mention Góa month and góiblót.

“It was the old custom in Svitjod to hold the main sacrifice in the Goi month in Uppsala. There sacrifices should be made for the peace and victories of the king. That's where the people from all over the Svear Empire should come, and at the same time the Thing of the Swedes should take place there.” -

Ólafs saga helga, chap. 77

Some say this Goi blot was a celebration of the return of vegetative forces - but this source makes no mention of that, and this would vary across Germanic Europe anyway according to latitude. Tonight is the full moon of February and the primroses and daffodils are already up here in West England, but perhaps this is not the case in Uppsala. Transferring a Norse calendar to the wider Germanic world may result in conflicts and anachronisms of this sort.

The second source is a fornaldarsögur which tells a different story. It says the Jotun King Fornjót, father of Ægir, the sea god, and who ruled Gotland, Kænland and Finnland, also had a daughter called Gói. There was a pious sacrificer called Thorri, who made a midwinter sacrifice called Thorra blót and one winter Gói disappeared at this blót - so they later had a sacrifice to find her and this was named góiblót but she did not appear. This seems to scream for a naturalistic interpretation; an obvious one, that Gói represents some green vegetation of a kind absent in midwinter, which people hope to see in Feb/March but don't if they live too far North!

In any case, tonight's Super moon is a holy night as is next month's and one of them is góiblót. Unfortunately we can't say precisely how góiblót should be performed. Obviously you must offer a sacrifice and pray for both peace, and victory for your leader in whatever battles your people are fighting at present. But to whom are the sacrifices and prayers offered? Gói? Perhaps a more familiar deity like Frigg? Some claim Góa month was known as women's month, and if so, then it seems proper to invoke a goddess on this festival.

Dr. Andreas Nordberg, an expert on the pagan lunar-solar calendar, believes that the Goa moon of Snorri's time was not the Goa moon of Heathen times which was in April. Nordberg writes:

"As well as Yule, the time of the disablot in Uppsala has also been the subject of much discussion. According to Adam of Bremen this event took place at “about the time of the vernal equinox”, whilst Snorri instead says that the event was held in the month of Gói, which lasted from mid-February to mid-March in the Icelandic calendar during Snorri’s lifetime. However, it is likely that the information given to Snorri did not refer to the Icelandic month, but the Swedish lunar month called Göje or Göja." (Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden Uppsala 2006, P.157)

"As well as Yule, the time of the disablot in Uppsala has also been the subject of much discussion. According to Adam of Bremen this event took place at “about the time of the vernal equinox”, whilst Snorri instead says that the event was held in the month of Gói, which lasted from mid-February to mid-March in the Icelandic calendar during Snorri’s lifetime. However, it is likely that the information given to Snorri did not refer to the Icelandic month, but the Swedish lunar month called Göje or Göja." (Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden Uppsala 2006, P.157)

Have I missed any other sources? Please let me know in the comments.

Labels:

anglo saxon paganism,

asatru,

blot,

calendar,

germanic peoples,

goddess,

Goiblot,

heathen,

iceland,

lunar,

Nordic,

Norse mythology,

Paganism,

sagas,

Viking Age

Thursday, 4 October 2018

The Living Wooden Idol that Speaks - Tremann

The word Trémann (tree man) appears several times in Norse sources, referring to some kind of living wooden idol. In Flateyjarbók, Ogmundr the Dane goes ashore at Samsey and finds a "trémann fornan" (ancient tree man) 140ft high and covered in moss and he wondered who worshipped this enormous god. In other cases the tremann is alive, such as in one story one is sent by pagan Hakon Jarl to kill Thorleifr Jarlaskald. This one was made from driftwood and dressed in human clothes with a human heart placed inside it and it was named Þorgarðr. The fact that Þorgarðr is referred to in a kenning as the Gautr of the battlefire, associates him with Odin, since Gautr is a name for Odin. In Havamal 49 a verse describes how Odin clothes two wooden men with the armour of noblemen, and in so doing turns them to demons of battle, presumably for his army in Valhöll.

There are other sources that associate Odin with the creation of idols that he makes live, such as The Old English gnomic poem Maxims I phrase 'Woden worhte weos' ('Woden made idols'’) and the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, who pretended that Odin was only a man, still admitted that he had the power to make inanimate statues speak.

All this was brought to my mind when I witnessed the funerary puppet dancing of the Batak people in Sumatra. Batak pagan priests made human-sized puppets which were dressed like those who had died and were manipulated by the Datu to dance, weep, gnash their teeth, and speak in the voice of the deceased. The puppets were used to revive souls of the dead and communicate with them. An extraordinarily Odinic form of necromancy. There is no historic link between Indonesia and the Odin cult of course, but the similarity is testament to the perennial nature of pagan truth. You can see it in my new video here.

There are other sources that associate Odin with the creation of idols that he makes live, such as The Old English gnomic poem Maxims I phrase 'Woden worhte weos' ('Woden made idols'’) and the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, who pretended that Odin was only a man, still admitted that he had the power to make inanimate statues speak.

All this was brought to my mind when I witnessed the funerary puppet dancing of the Batak people in Sumatra. Batak pagan priests made human-sized puppets which were dressed like those who had died and were manipulated by the Datu to dance, weep, gnash their teeth, and speak in the voice of the deceased. The puppets were used to revive souls of the dead and communicate with them. An extraordinarily Odinic form of necromancy. There is no historic link between Indonesia and the Odin cult of course, but the similarity is testament to the perennial nature of pagan truth. You can see it in my new video here.

Labels:

anglo-saxon,

anthropology,

Batak,

Havamal,

heathen,

Idols,

indo-european,

indonesia,

odin,

odinic,

Paganism,

prose edda,

Religion and Spirituality,

sagas,

Sumatra

Saturday, 4 October 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)