A review of Vilhelm Grønbech's seminal work on the religion and culture of ancient Germanic peoples. Grønbech, professor of the history of religion at the University of Copenhagen, looks at Norse, Lombardic, Anglo-Saxon, Gothic and Roman sources to identify a common Teutonic culture focused on luck, honour, shame, kinship, and a unique perspective on the afterlife and the soul. My review includes favourite quotes from volume 1 of the two part book republished by Antelope Hill.

Showing posts with label anglo saxon paganism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label anglo saxon paganism. Show all posts

Monday, 26 May 2025

Wednesday, 22 May 2024

Thursday, 16 May 2024

How to be a Heathen? Asatru online course

Starting Heathenry

Starting Heathenry is a NEW ritual-focused online course which will furnish you with the knowledge and confidence you need to practise the Germanic Heathen religion alone or with others, making wise decisions about worship based on reliable historical evidence.

The course teaches you how to construct Heathen prayers for yourself, not according to the established rites of any modern group, but according to what historical sources show. Starting Heathenry assumes you are interested in Germanic paganism, know about the gods and myths, and want to begin practising this religion, but require guidance on how to do so.

|

| Key points are displayed in videos as bullet-points to help you remember them |

Micro-learning

A modern way of learning an ancient religionStarting Heathenry is based on a micro-learning structure which is proven to improve knowledge retention by 18-80% in students compared to other learning methods. The 10 lessons include over 50 videos, and quizzes to access from your phone or computer. Absorb more than 5 hours of learning material bit by bit, as it suits you. Within just 20 minutes after a hearing a lecture or reading a book, 50% of newly learned information is forgotten. Over the next 9 hours, that number drops by a further 10%, and after a month, only 24% of the information remains without revision or repeat learning. Micro-learning is designed so you retain the knowledge over a long period. I previously worked on crafting such learning material for the WHO to help health care professionals learn about the dangers of side effects from medicines. Now I am using the same technique to help Heathens learn to worship the gods of their ancestors.

Enroll today. Your path to knowing the gods through ritual starts here.

Thursday, 7 September 2023

How to set up a Heathen Altar in your Home : Paganism 101

A guide for setting up an altar to the gods inside your home which you can use for domestic worship. Many people are requesting this kind of content and its been nearly six years since I last made a video like this, so here you go!

Friday, 14 October 2022

Anglo-Saxon roots of British Monarchy and the Coronation Ceremony

His Majesty Charles III, King of the United Kingdom, will be crowned in May 2023 in a ritual which is nearly 1050 years old! The British monarchy and the ritual of coronation both have their origins in Anglo-Saxon England and its pagan kings who claimed descent from the King of the gods - Woden who the Vikings called Odin. In this video you will learn all the pagan elements that have survived in the modern coronation ritual - some of which date back to Ancient Rome!

Art:

Raven god by Christian Sloan Hall

Sky father by Andrew Whyte

Wartooth Viking by Christian Sloan Hall

Odin and Sleipnir by Christopher Steininger

Odin and dead by Christian Sloan Hall

Hengist and Horsa by Graman

Chaney, William, The Cult of Kingship in Anglo-Saxon England: The Transition from Paganism to Christianity, (Manchester University Press: 1970)

Dumville, David. N., 'Kingship, Genealogies and Regnal Lists' in Early medieval kingship, P.H. Sawyer & I.N. Wood (eds), (Leeds: 1977).

Eliade, M. ‘The Myth of the Eternal Return’ (1954).

Faulkes, A., Six papers on The Prose Edda: Descent from the gods. 2nd ed, (Viking society for northern research: 2007).

HENRY MAYR- HARTING, 'The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England, (3rd ed. Philadelphia, 1991) Bath Press.

Rowsell, T., “Woden and his Roles in Anglo-Saxon Royal Genealogy”, University College London, (2012).

Sky father by Andrew Whyte

Wartooth Viking by Christian Sloan Hall

Odin and Sleipnir by Christopher Steininger

Odin and dead by Christian Sloan Hall

Hengist and Horsa by Graman

Sources:

Chaney, William, The Cult of Kingship in Anglo-Saxon England: The Transition from Paganism to Christianity, (Manchester University Press: 1970)

Dumville, David. N., 'Kingship, Genealogies and Regnal Lists' in Early medieval kingship, P.H. Sawyer & I.N. Wood (eds), (Leeds: 1977).

Eliade, M. ‘The Myth of the Eternal Return’ (1954).

Faulkes, A., Six papers on The Prose Edda: Descent from the gods. 2nd ed, (Viking society for northern research: 2007).

HENRY MAYR- HARTING, 'The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England, (3rd ed. Philadelphia, 1991) Bath Press.

Rowsell, T., “Woden and his Roles in Anglo-Saxon Royal Genealogy”, University College London, (2012).

Thursday, 30 December 2021

Belief in the Unknown and Unknowable

Once more, before I move on

and set my sights ahead,

in loneliness I lift my hands up to you,

you to whom I flee,

to whom I, in the deepmost depth of my heart,

solemnly consecrated altars

so that ever

your voice may summon me again.

Deeply graved into those altars

glows the phrase: To The Unknown God.

I am his, although I have, until now,

also lingered amid the unholy mob;

I am his—and I feel the snares

that pull me down in the struggle and,

if I would flee,

compel me yet into his service.

I want to know you, Unknown One,

Who reaches deep into my soul,

Who roams through my life like a storm—

You Unfathomable One, akin to me!

I want to know you, even serve you.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, 1864. Translated by Michael Moynihan

Nietzsche here frankly expresses a strikingly honest form of spirituality which I believe typified the highest sentiments of the Indo-European spiritual worldview. It combines faith, which most religions require, with an honest appraisal of what is truly known of the divine by mortals. In this case the existence of the god is unquestioned, but the exact nature or even the name of the god are not known.

In this post I will provide some examples of this heroic spiritual view of the divine and of death. Consider the Nāsadīya Sūkta also known as the Hymn of Creation, the 129th hymn of the 10th mandala of the Rigveda (10:129). In it, the speaker or singer asks philosophical questions about Creation, and answers himself - we do not know and maybe even the creator himself does not know.

1. Then even non-existence was not there, nor existence,

There was no air then, nor the space beyond it.

What covered it? Where was it? In whose keeping?

Was there then cosmic fluid, in depths unfathomed?

2. Then there was neither death nor immortality

nor was there then the torch of night and day.

The One breathed windlessly and self-sustaining.

There was that One then, and there was no other.

3. At first there was only darkness wrapped in darkness.

All this was only unillumined cosmic water.

That One which came to be, enclosed in nothing,

arose at last, born of the power of knowledge.

4. In the beginning desire descended on it -

that was the primal seed, born of the mind.

The sages who have searched their hearts with wisdom

know that which is, is kin to that which is not.

5. And they have stretched their cord across the void,

and know what was above, and what below.

Seminal powers made fertile mighty forces.

Below was strength, and over it was impulse.

6. But, after all, who knows, and who can say

Whence it all came, and how creation happened?

the gods themselves are later than creation,

so who knows truly whence it has arisen?

7. Whence all creation had its origin,

the creator, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not,

the creator, who surveys it all from highest heaven,

he knows — or maybe even he does not know.

This reflects the religious attitude of the Bronze Age Aryan, in which no insincere claims are made about what can actually be known with any certainty by mere mortals. Obviously this is less consoling than a religion which claims to have all the answers, but in this spiritual worldview, truth comes first.

This same attitude is evident in Greece where there was a shrine to the unknown God at the Areopagus. St Paul exploits this in his sermon, twisting the pagan honesty about that which is unknown of the divine, and calling this a failing of the pagan faith.

"As I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: TO AN UNKNOWN GOD. So you are ignorant of the very thing you worship — and this is what I am going to proclaim to you."

Either in ignorance, or as a technique of deception, Paul missed the pious and honest religious meaning of celebrating that which is unknown and unknowable of the divine by mortals. Christianity can not accommodate this kind of expression of faith, if it did we should see Christian prayers where they ask frank questions about what it is possible for them to know with certainty:

"Did the angel really appear to Mary or was it a daemon? We cannot say.

Was Jesus really a god or was he possessed by a daemon? It cannot be known.

Is YHWH the only god or is he lying? Maybe even He himself doesn’t know for sure.”

Instead, even uttering such things is called heresy. The Bible and the Abrahamic faiths in general provide only a tautological argument that their claims are true because of the scripture and that the scripture is true because it says it is true.

We have seen how Christianity exploited the frank admission by Greek pagans of what can be known of the divine by manipulating the less secure and less knowledgeable pagans who longed for consoling answers to the great unanswerable questions. I believe the same thing occurred 700 years later in England.

In Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, Bede describes how the pagan King Edwin of the Northumbrians calls a council of his wisest retainers to debate whether they should convert to Christianity and it is at this point that one of the "king's chief men" gave the following speech:

“The present life of man upon earth, O King, seems to me in comparison with that time which is unknown to us like the swift flight of a sparrow through the mead-hall where you sit at supper in winter, with your Ealdormen and thanes, while the fire blazes in the midst and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest, but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter to winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follow or what went before we know nothing at all.”Evidently the anecdote is provided by Bede as an example of a pagan feeling hopeless with the uncertainty of pagan beliefs, and thus wanting something more solid in the form of Christian doctrine. However, this story is intended to impress pagans and encourage them to convert and is part of a conversion narrative, therefore we should expect to see in it tropes that would be recognised by pagans. For that reason I believe that Bede has used a well known pagan poetic metaphor about the uncertainty of life, not only after death, but before birth! I have covered in my videos how Germanic and Celtic pagans believed in a form of reincarnation so the fate of the “soul” prior to birth was also a concerning question for them.

The idea that this passage was just an expression of Christian belief is unsatisfactory because Christians do claim to know the fate of the soul after death and they certainly do not consider that souls have a similar existence prior to birth as they do after death. The possibility that this passage is a modified pagan metaphor, misrepresented by Bede in a similar way to how Paul had misrepresented the unknown god, seems very likely and it is therefore mysterious to me that no other historian has suggested it (as far as I am aware). The passage was, after all, put in the mouth of a pagan Anglo-Saxon, so why should we not presume it is intended to reflect a pagan world view to some extent?

I am also convinced it has pagan provenance because it matches the heroic and frank attitude toward death and the divine which is seen elsewhere in Indo-European religions and which I have outlined above.

The same heroic, Indo-European fatalistic resolve in the face of death survives in Buddhism and is beautifully portrayed in the film Kagemusha by Kurosawa. In the scene below, Oda Nobunaga the demon king, quotes the following lines:

"Human life lasts only 50 years, compare it with the life of Geten (a form of Buddhist paradise, where one day lasts years of our world), it is truly a dream and an illusion. Life, once given, cannot last forever”

The text recited by Oda Nobunaga is from a Japanese Noh play called "Atsumori" which was named after Taira no Atsumori, a Taira soldier who died during the Gempei war 1180-1185 (Taira vs Minamoto clan). The Oda clan claimed descent from the Taira and this dance and song is famous for having been recited by Oda Nobunaga which is why Kurosawa included it in Kagemusha. Watching this performance, I can imagine the story of the sparrow in the hall was sung in a similar way, in a meadhall by a scop to all the Thegns and the Lord. I imagine them moodily pondering the unknowable destiny of the soul as the scop strummed his lyre and recited the holy verses.

Thursday, 22 April 2021

Pagan English folk music with Dan Capp of Wolcensmen

Dan Capp's Wolcensmen creates heathen hymns from the mists of England. He was originally known as a member of the Anglo-Saxon themed metal band Winterfylleth but his acoustic side project Wolcensmen is now the focus of his work. Dan’s music evokes the persistent paganism in the folk ways of the peasants of England, and breathes life into a natural expression of the English folk soul. In this interview we discuss a few of his songs and the meaning of the pagan themes in his lyrics.

This podcast is also available on Apple podcasts, Spotify and the rest!

This podcast is also available on Apple podcasts, Spotify and the rest!

Thursday, 1 April 2021

Anglo-Saxon Paganism: Elves, ents, orcs

Art:

Thomas Cormack - Elf blot

Christian Sloan Hall - Hel, orcs, Odin, draugr

Christopher Steininger - Idunn, boat animation, mead-hall

Robert Molyneaux - Yeavering temple animation

Christopher Steininger - Idunn, boat animation, mead-hall

Robert Molyneaux - Yeavering temple animation

Sources:

Abram, C. ‘In Search of Lost Time: Aldhelm and The Ruin’, Quaestio (Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic), vol. 1, 2000.

Dowden, Ken (2000). European Paganism: The Realities of Cult from Antiquity to the Middle Ages.

Doyle, Conan. (2018). Dweorg in Old English: Aspects of Disease Terminology.

Gunnel, T., ‘How Elvish were the Elves?’ 2007.

Hall, A., 'Are there any Elves in Anglo-Saxon Place-Names?', Nomina: Journal of the Society for Name Studies in Britain and Ireland, 29 (2006), 61-80.

Hall, A., (2004). The Meanings of Elf, and Elves, in Medieval England. 2007.

Lund, J., "At the Water's Edge" in "Signals of Belief in Early England"

Lysaght, P. ‘the banshee: the irish supernatural death messenger’

North, R. 1997 Heathen gods in Old English literature.

Pollington, S. 2011. The Elder Gods: The Otherworld of Early England.

Price, Neil & Mortimer, Paul. (2014). An Eye for Odin? Divine Role-Playing in the Age of Sutton Hoo. European Journal of Archaeology.

Semple. S., A Fear of the Past: The Place of the Prehistoric Burial Mound in the Ideology of Middle and Later Anglo-Saxon England. (1998)

Monday, 8 March 2021

Anglo-Saxon Paganism: Gods

What were the pre-Christian religious traditions of England like? This two part series serves as an introduction to Anglo-Saxon paganism. In this podcast we will look at the evidence we have for the pagan gods of the Anglo-Saxons and will compare them to what we know about the Norse equivalents that Vikings worshipped. At times it is also necessary to use Indo-European comparative mythology to understand the gods and goddesses of the Anglo-Saxons. “Anglo-Saxon paganism” refers to the Germanic pagan traditions brought to Britain in the 5th century and which persisted in surprising ways even after the Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England over the 7th and 8th century.

Thanks to Wulfheodenas for modelling their Vendel era Germanic weapons and clothing.

Art:

Alex Cristi - Erce.

Andrew Whyte - Nehalennia.

Christian Sloan Hall - Eastre

.

Gramanh Folcwald - Hengist and Horsa.

Hungerstein - Tiw.

Robert Molyneaux - Yeavering temple

.

Ryan Murray - Modra.

1st Aquarian - Migration map.

Sources:

Chaney, W. A. 1972. The Cult of Kingship in Anglo-Saxon England: The Transition from Paganism to Christianity, The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory, 47:2, 141-143.

Das, R. et al. 2016. Localizing Ashkenazic Jews to Primeval Villages in the Ancient Iranian Lands of Ashkenaz, Genome Biology and Evolution, Volume 8, Issue 4.

Dowden, K. 2000. European Paganism: The Realities of Cult from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. London and New York: Routledge. p. 229.

Dumezil, G. 1988. ‘Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty’

Ealdorblotere, T. 2020. To Hold the Holytides.

Faussett, B. 1856, Inventorium Sepulchrale. An Account of Some Antiquities dug up at Gilton, Kingston, Sibertswold, Bafriston, Beakesbourne, Chartham, and Crundale, in the County of Kent, from A.D. 1757 to A.D. 1773 (London 1856).

Grimm, J. 1835. Deutsche Mythologie.

Kemble, J. M. 1876. The Saxons in England.

Kershaw, K. 2000. ‘The one-eyed god: Odin and the (Indo-)Germanic Männerbünde’ (Journal of Indo-European studies monograph).

Nordberg, Andreas. 2006. Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning: Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden. Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur: Uppsala.

North, R. 1997 Heathen gods in Old English literature. Cambridge University Press.

Pollington, S. 2011. The Elder Gods: The Otherworld of Early England.

Reaves, W. 2018. Odin's Wife: Mother Earth in Germanic Mythology.

Rowsell, T. 2011. Woden and his Roles in Anglo-Saxon Royal Genealogy.

Schiffels, S., Haak, W., Paajanen, P. et al. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nat Commun 7, 10408 (2016).

Stenton, F. 1943. Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford.

Werner, J. 1964. Herkuleskeule und Donar-Amulett. Jahrb. RGZM 11, 176–197.

Saturday, 2 January 2021

The Royal Indo-European Horse Sacrifice

The most important sacrificial animal in the original Indo-European religion was the horse - The very power of their kings depended on an elaborate ritual horse sacrifice. In this video we will look at the rite of horse sacrifice in various Indo-European traditions in order to get an idea of why the Proto-Indo-Europeans considered it such an important royal ritual and what it looked like. Beginning with the enormous Ashvamedha in India, and moving on to Rome's October Horse rite and ending on old Norse written sources combined with archaeological evidence from the Nordic Bronze age through to the Viking age - we get a pretty clear picture of the gruesome and often sexual rituals associated with the inauguration of kings and the necessary solar horse sacrifice. This video is mainly based on the recent book on the same subject by Kaliff & Oestigaard.

Sources:

Dumézil, G. 1970. ‘Archaic Roman Religion. Volume One.’ The John Hopkins University Press. Baltimore and London. Eliade, M. 1993. ‘Patterns in Comparative Religion.’ Sheed and Ward. New York. Eliade, M., ed., ‘Encyclopedia of Religion’ (NY: Collier Macmillan, 1987), VI:463; Kaliff, A., & Oestigaard, T., ‘The Great Indo-European Horse Sacrifice: 4000 Years of Cosmological Continuity from Sintashta and the Steppe to Scandinavian Skeid’ (2020) Outram, A., et al. ‘Horses for the dead: funerary foodways in Bronze Age Kazakhstan’ - (March 2011) Puhvel, J., ‘Comparative Mythology’ 1987 Rowsell, T., Riding To The Afterlife: The Role Of Horses In Early Medieval North-Western Europe. (2012) Sikora, M., ‘Diversity in Viking Age horse burial’ in The Journal of Irish Archaeology(Belfast: 2003-4). P.87. Solheim, S. 1956. Horse-fight and horse-race in Norse tradition. Studia Norvegica No. 8. H. Aschehoug & Co. (W. Nyaard). Oslo. Veil, Stephan & Breest, Klaus & Grootes, P. & Nadeau, Marie-Josée & Huels, Matthias. (2012). A 14 000-year-old amber elk and the origins of northern European art. Antiquity. 86. 660-673.Wednesday, 1 July 2020

Is Devon Celtic? What's the difference between Devon and Cornwall?

EDIT: Since writing this blog post a thorough genetic study of ancient British and Anglo-Saxon samples has been published by Gretzinger et al (2022). The data in the supplements show that the people of Devon are about 37% Early Anglo-Saxon (CNE), 35% Iron Age Briton (WBI), and 26% Medieval French (CWE) meaning the Germanic ancestry is their dominant component. Cornwall is estimated to be 21% CNE 51% WBI and 26% French

There are some people who erroneously insist that Devon, like Cornwall, was founded on a Celtic rather than English identity. One such individual is attempting to rewrite local history on Wikipedia to claim that Devon is not English. That is simply not the case. Devon has more Anglo-Saxon DNA than Cornwall does, and has not preserved any Celtic language at all. In fact the Devon dialect uniquely preserves some archaic Old English elements which have been lost elsewhere, about which you can learn in the video below.

There are some people who erroneously insist that Devon, like Cornwall, was founded on a Celtic rather than English identity. One such individual is attempting to rewrite local history on Wikipedia to claim that Devon is not English. That is simply not the case. Devon has more Anglo-Saxon DNA than Cornwall does, and has not preserved any Celtic language at all. In fact the Devon dialect uniquely preserves some archaic Old English elements which have been lost elsewhere, about which you can learn in the video below.

Labels:

anglo saxon,

anglo saxon paganism,

barnstaple,

celtic,

devon,

Devonshire,

history,

Norse,

Paganism,

Viking

Location:

Barnstaple, UK

Tuesday, 16 June 2020

From Runes to Ruins (2014) / Watch Online

Watch From Runes to Ruins (2014) online for free.

Thursday, 30 April 2020

Odin and the Horned Spear-Dancer

Viking and Anglo-Saxon artwork often includes a man with bird shaped horns. This mysterious figure is known as the horned man or the weapon dancer. The motif shows up in various different contexts and over a huge geographic range and timeframe - from early Anglo-Saxon England to Viking age Russia. It is commonly associated with the cult of the Nordic god Odin or the Anglo-Saxon god Woden and with extraordinary shamanic rituals as I shall explain in this video.

Sources:

- Mortimer, Paul, 'What Colour a God's Eyes' (2018)

- Oehrl, Sigmund, 'Horned ship-guide – an unnoticed picture stone fragment from Stora Valle, Gotland' (2016)

- Oehrl, Sigmund, 'DOCUMENTING AND INTERPRETING THE PICTURE STONES OF GOTLAND' (2017)

Artwork

The following paintings of the horned spear dancer are by Hungerstein.

Friday, 14 February 2020

Podcast: Interview with Ralph Harrison of the Odinist Fellowship

This Podcast is also available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Podbean, Player FM and all good podcasting apps and platforms.

Ralph Harrison has been an Odinist for 40 years. He is the Director of the Odinist Fellowship, the UK’s only registered charity for the indigenous faith of the English people. They acquired a 16th century chapel in Newark which was consecrated on Midsummer's Day 2014 as the first heathen Temple in England for well over a thousand years. You can donate to the charity or the temple using the links below. Ralph and I had a nice chat about the Heathen religion, its rise in popularity in recent years due to the success of TV programs like Vikings, and also the dangers the faith faces from new age influences like Wicca and naturalism.

Contact the Odinist Fellowship

Email OF website

Address:

ODINIST FELLOWSHIP,

B.M. EDDA,

LONDON WC1N 3XX.

Newark Temple website

Newark Temple Facebook page

Saturday, 8 February 2020

Góa month and góiblót - February, March or April festival?

|

| Frigg weaves |

While some modern heathens choose to match ancient Germanic festivals with the Gregorian calendar, others try to stick to the lunar-solar calendar the Germanic people observed.

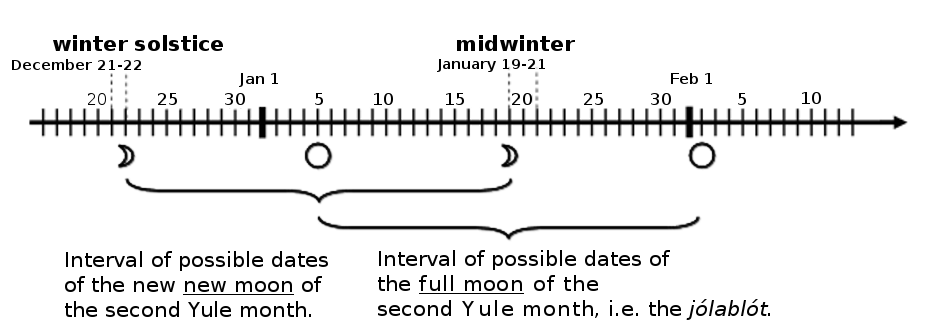

There are some problems calculating Góa month in either case, due to lack of sources on the festival. The month of Góa is alleged to have been the penultimate month of winter, according to the old, Norse calendar used in Iceland. According to some Icelanders, góiblót took place in late February - but if we follow the lunar-solar model then it would have been on the full moon, because the full moon marks the high festival of each month, and the new moon marks the start of the month, making the start of this year's Góa month either 23rd Jan, or 22nd Feb, ending either 22nd Feb or 23rd March 2020 - with the final month of winter ending in April when the rites of the start of Summer were held - associated with Easter-month in Anglo-Saxon England and all the variant May day celebrations across Europe.

So February seems to match up well enough for the dating, although I am unsure where the claim it is the penultimate month of winter originates. I know of two sources that mention Góa month and góiblót.

“It was the old custom in Svitjod to hold the main sacrifice in the Goi month in Uppsala. There sacrifices should be made for the peace and victories of the king. That's where the people from all over the Svear Empire should come, and at the same time the Thing of the Swedes should take place there.” -

Ólafs saga helga, chap. 77

Some say this Goi blot was a celebration of the return of vegetative forces - but this source makes no mention of that, and this would vary across Germanic Europe anyway according to latitude. Tonight is the full moon of February and the primroses and daffodils are already up here in West England, but perhaps this is not the case in Uppsala. Transferring a Norse calendar to the wider Germanic world may result in conflicts and anachronisms of this sort.

The second source is a fornaldarsögur which tells a different story. It says the Jotun King Fornjót, father of Ægir, the sea god, and who ruled Gotland, Kænland and Finnland, also had a daughter called Gói. There was a pious sacrificer called Thorri, who made a midwinter sacrifice called Thorra blót and one winter Gói disappeared at this blót - so they later had a sacrifice to find her and this was named góiblót but she did not appear. This seems to scream for a naturalistic interpretation; an obvious one, that Gói represents some green vegetation of a kind absent in midwinter, which people hope to see in Feb/March but don't if they live too far North!

In any case, tonight's Super moon is a holy night as is next month's and one of them is góiblót. Unfortunately we can't say precisely how góiblót should be performed. Obviously you must offer a sacrifice and pray for both peace, and victory for your leader in whatever battles your people are fighting at present. But to whom are the sacrifices and prayers offered? Gói? Perhaps a more familiar deity like Frigg? Some claim Góa month was known as women's month, and if so, then it seems proper to invoke a goddess on this festival.

Dr. Andreas Nordberg, an expert on the pagan lunar-solar calendar, believes that the Goa moon of Snorri's time was not the Goa moon of Heathen times which was in April. Nordberg writes:

"As well as Yule, the time of the disablot in Uppsala has also been the subject of much discussion. According to Adam of Bremen this event took place at “about the time of the vernal equinox”, whilst Snorri instead says that the event was held in the month of Gói, which lasted from mid-February to mid-March in the Icelandic calendar during Snorri’s lifetime. However, it is likely that the information given to Snorri did not refer to the Icelandic month, but the Swedish lunar month called Göje or Göja." (Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden Uppsala 2006, P.157)

"As well as Yule, the time of the disablot in Uppsala has also been the subject of much discussion. According to Adam of Bremen this event took place at “about the time of the vernal equinox”, whilst Snorri instead says that the event was held in the month of Gói, which lasted from mid-February to mid-March in the Icelandic calendar during Snorri’s lifetime. However, it is likely that the information given to Snorri did not refer to the Icelandic month, but the Swedish lunar month called Göje or Göja." (Jul, disting och förkyrklig tideräkning Kalendrar och kalendariska riter i det förkristna Norden Uppsala 2006, P.157)

Have I missed any other sources? Please let me know in the comments.

Labels:

anglo saxon paganism,

asatru,

blot,

calendar,

germanic peoples,

goddess,

Goiblot,

heathen,

iceland,

lunar,

Nordic,

Norse mythology,

Paganism,

sagas,

Viking Age

Monday, 12 August 2019

Horse-healing magic from the steppes

I have long known of the second Merseberg charm, one of two which constitute the only surviving pagan verses in Old High German. As with most Germanic pagan things, we only have it by chance; a cleric at an abbey happened to put it in a liturgical book in the 10th century. We can be sure the charm, a cure for an injured horse, dates to many centuries earlier because it actually invokes seven pagan gods.

Phol ende uuodan uuorun zi holza.

du uuart demo balderes uolon sin uuoz birenkit.

thu biguol en sinthgunt, sunna era suister;

thu biguol en friia, uolla era suister;

thu biguol en uuodan, so he uuola conda:

sose benrenki, sose bluotrenki, sose lidirenki:

ben zi bena, bluot si bluoda,

lid zi geliden, sose gelimida sin!Later I discovered that this charm, written in Christian times, did not merely date to the days of Germanic paganism, but far further back. The evidence is in in Book IV/12 of the Atharva-Veda, compiled in India between 1200 BC - 1000 BC.

Phol and Wodan were riding to the woods,

and the foot of Balder's foal was sprained

So Sinthgunt, Sunna's sister, conjured it;

and Frija, Volla's sister, conjured it;

and Wodan conjured it, as well he could:

Like bone-sprain, so blood-sprain, so joint-sprain:

Bone to bone, blood to blood, joints to joints, so may they be glued

I do not think for a moment that the Germanic charm is derived from the Vedic source. I find it far more likely both derive from a charm belonging to the Yamnaya culture on the Neolithic Eastern European steppes which was originally for horses, as in the case of the Merseberg charm, and that it was adapted in India for human use. It has been established that Yamnaya were late Proto-Indo-European speakers and are responsible for the modern domestic horse, so they were of course the first to develop magic for the aid of horses, and this would have spread with the horses, religion and Indo-European languages.Rohan! art thou, causing to heal (rohanî), the broken bone thou causest to heal (rohanî): cause this here to heal(rohaya), O arundhatî!That bone of thine which, injured and burst, exists in thy person, Dhâtar shall kindly knit together again, joint with joint!Thy marrow shall unite with marrow, and thy joint (unite) with joint; the part of thy flesh that has fallen off, and thy bone shall grow together again!Thy marrow shall be joined together with marrow, thy skin grow together with skin! Thy blood, thy bone shall grow, thy flesh grow together with flesh!Fit together hair with hair, and fit together skin with skin! Thy blood, thy bone shall grow: what is cut join thou together, O plant!Do thou here rise up, go forth, run forth, (as) a chariot with sound wheels, firm feloe, and strong nave; stand upright firmly!If he has been injured by falling into a pit, or if a stone was cast and hurt him, may he (Dhâtar, the fashioner) fit him together, joint to joint, as the wagoner (Ribhu) the parts of a chariot!

Today I was made aware of another cognate for the charm; this time from Ireland, an account contributed by a school child in county Cork in 1938.

There was an old woman named Layng that lived near this school and she had cure of the sprain. These are the words of the charm. "Our Lord God went a hunting through moors and through mountains. His foals foot wrested, he sat down and blessed it, saying from bone to bone, from flesh to flesh every sinew in its own place." She used rub the sprain very much while saying these words and she would say the Lords Prayer." She was a protestand. She left the charm to some men around this place. Some of the old people had charms for stopping blood, toothache, rash, St. Anthony's fire, choking and one very old man heard a charm for making rats come out of their holes and cut their necks with a razor.Now, the fact she was a Protestant, and that as far as I am aware Layng is a name of Scottish origin, brought to Ireland by Scottish immigrants, makes me hesitant to ascribe this to an ancient Irish tradition. I consider three possible explanations.

- That this is of West-Germanic origin, like the Merseberg charm, and was brought to Scotland by Anglo-Saxons.

- That this is a North Germanic cognate brought to Scotland by Vikings.

- This is a Scots-Celtic cognate charm from the same Indo-European root as the Germanic and Vedic ones.

The woman invoked "Our Lord God" which is not only a common epithet of the Christian God, but also a name for Odin. I am not aware of a Celtic god who is invoked by this name. There are at least 10 more examples of charms in recorded Irish folklore which follow the same formula.

There is also an example from Sweden written down in 1860 which may be a Northern cognate if it is not derived from the West Germanic one.

Dåve red över vattubro,

Så kom han in i Tive skog;

Hästen snava mot en rot

och vrickade sin ena fot.

Gångande kom Oden:

- Jag skall bota dig för vred,

kött i kött, ben i ben,

jag skall sätta led mot led,

och din fot skall aldrig sveda eller värka mer

Dåve rode over Vattubro, then he came into Tive woods; the horse tripped on a root and sprained one of his feet. Odin came walking: I will cure you for sprain, meat to meat, bone to bone, I will put joint to joint, and your foot shall never sting or hurt again.

And another from 19th century Sweden which invokes the goddesses:

Fylla red utför berget, hästen vred sin vänstra fot, så mötte hon Freja. – Jag skall bota din häst. Ur vred, ur skred, i led! Jag skall bota dig för stockvred, stenvred, gångvred, ont ur kött, gott i kött, ont ur ben, gott i ben, gott för ont, led för led, aldri mer skall du få vred! Fylla rode down the hill, the horse sprained its left foot, then she met Freja. I will cure your horse. Out sprain, out fall, in joint! I will heal you from log sprain, stone sprain, walk sprain bad out of flesh, good into flesh bad out of bone, good into bone good for bad, joint for joint, never again shall you have sprain!In 2013 I read one of my poems in a cafe in London. As you can hear, it was very much influenced by this magic charm...

Labels:

"anglo saxons",

anglo saxon paganism,

asatru,

folklore,

germanic peoples,

heathen,

hindu,

hinduism,

horse,

indo-european,

ireland,

irish folklore,

magic,

Norse mythology,

odin,

vedic,

wotan,

yamnaya

Monday, 1 April 2019

Easter and May day are pagan

Now begins Eastermonth! This is an entire month which the Anglo-Saxons devoted to the goddess Ēastre. Her name is not, as some erroneously claim, related to the Semitic goddess Ishtar, nor to the hormone estrogen, but is in fact Germanic. Ēastre, or as she is known in modern English, "Easter" was equivalent to the continental German goddess Ostara and both names are derived from that of the ancient Indo-European goddess of dawn *H₂ewsṓs (→ *Ausṓs), from whom the Vedic goddess of dawn, Ushas, is also derived. One of the holy names of Ushas was Bṛhatī (बृहती) "high" which is cognate with Proto-Celtic *Brigantī meaning "The High One", and the name of a British goddess Brigantia (Brigid). The Greek goddess Ēōs, Baltic goddess Aušrinė and Roman goddess Aurora are all etymologically derived from the same IE word and likely from the same PIE goddess. The month is attested by Anglo-Saxon monk Bede, who said feasts of the goddess were celebrated in April, but when we can only guess. There is no reason to believe it was on the exact day Christians now celebrate Easter. Some aspects of Christian Easter resemble paganism because the symbolism of eternal life and rebirth are important for both. The Roman pagans had a flower festival called Floralia on 27th April which may well have had equivalents in Britain, but surely the largest celebration for the dawn goddess was at the end of the Easter month on the eve of May day which heralds the dawn of summer. I consider May day, or specifically the night before it, to be the climax of Eastermonth and a holy celebration to this sacred goddess. I have covered the diverse celebration of May day around the world in a video already (see link below). The photo above is shows the May queen in Devon in 1955, a young girl who symbolises the dawn goddess Easter who heralds the start of Summer, and the May pole which is a phallic fertility symbol.

I would also speculate that since, in Celtic and Germanic countries, the folk culture around May eve has focused heavily on sexuality, even in recent times, usually of an unbridled sort normally prohibited by Christian morality, and since the cult of Aurora was often invoked in sexual poetry, we might well assume that the cult of Easter had a heavy emphasis on the sexuality and fertility of young people, especially women. The Greek Eos was cursed by Aphrodite with unsatisfiable sexual desire causing her to abduct handsome young men - a promiscuity very reminiscent of an account of May eve among the English in the early modern era by a puritan who wrote that on that night "Scarcely a third of maidens going to the woods returned home undefiled", similar account are recorded in Ireland. The fecundity of the earth is tied explicitly to that of the wombs of nubile girls of the community. For this reason a sort of transgressive sexuality becomes temporarily permissible due to the divine associations of sex on this night.

Tuesday, 12 February 2019

Saturday, 22 December 2018

Folk Horror - Interview with Tom Rowsell

This interview was first published on the Folk Horror Revival blog.

Firstly can you tell us a little about yourself – your background, how you ended up as a writer and involved with graphic novels?

I come from a media background; used to be a writer for trendy magazines in London and wanted to be a film maker. I started out directing horror films and music videos with zombies in the English countryside and wrote my dissertation for my Media degree in 2007 on representation of rural communities in horror films of the seventies. In 2011 I quit my media job and went back to University to study paganism of the Germanic peoples and subsequently directed and presented a documentary film on the subject called From Runes to Ruins (2014). I grew up reading graphic novels; 2000 AD and Alan Moore etc. So when I was approached by Christopher Steininger, a Canadian artist asking to collaborate on a comic book project, I was delighted. I immediately suggested a folk horror story for Christmas.

Who are your influences/heroes? (as a writer and in general)

In film making I was very influenced by everyone from Ingmar Bergman to Piers Haggard. My presenting style is based on old pedagogical BBC TV; people like Kenneth Clarke and David Attenborough but mixed with Jonathan Meades’ cheeky humour. My writing for this particular work was deliberately based heavily on Dickens’ A Christmas Carol but also on the old BBC ghost stories for Christmas.

Do you consider your work to fit into the Folk Horror genre and if so what is it about it that you feel fits that label?

Absolutely. I have a personal connection to the genre; my grandfather’s farm was near Kirkcudbright where The Wicker Man was filmed, and I knew all the places from the film. By the time I went to university, I was obsessed with it, which is why I had to include it in my dissertation. It had previously influenced all the horror films I made as a teen, which depicted the English landscape as pregnant with the horror of history. That was over a decade ago and since then I have become more passionate about the genre, although I have not made any horror for a long time. This book was consciously written as a part of the Folk Horror genre, so the terror derives from the pagan roots of the land’s history.

Do you have a particular process (ritualistic or preparatory) when are working on a particular project? Any way in which you get yourself in `the zone’ or work up ideas?

Sometimes I can’t write and sometimes I can. David Lynch says concepts of the sphere of pure ideas come to him from "the unified field" which is an ocean of pure consciousness from which he says "everything comes". I have similar views. I don’t feel like my ideas are my own, and I’m not interested in being original, just communicating ideas from that realm in different ways so they can be understood by different people.

Can you give an outline of the content of Spirit of Yule and how/why you ended up creating it? So the cartoon came out first (almost a year ago) and the book this year. Was that always the plan?

In both the motion comic and the graphic novel, the reader, guided by The Green Knight, travels back through the centuries to learn the pagan roots of Yuletide; from the Dickensian, to the Arthurian and back to the Anglo-Saxons and Norse. The ghost story is set in Victorian England on Christmas Eve, but it teaches the reader all about how pagan people in England used to celebrate Yule 1300 years ago. I based all the pagan practices depicted in the story on contemporary accounts of Yule celebrations among Norse pagans, so this is not only entertainment, but also a kind of educational tool, suitable for all ages (provided they don’t mind a bit of horse blood!). Someone commented on the cartoons saying it ought to be a book, so Christopher grabbed that ball and ran with it. We struggled to get it all ready and self-publish in time for this Christmas though!

What is next?

Christopher and I will work on another graphic novel in future, this time on comparative mythology of different Indo-European traditions; Celtic, Hindu, Greek etc. He is a versatile artist, so I am excited to see what he comes up with for the next project!

The Spirit of Yule is available to purchase here

Sunday, 15 April 2018

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)